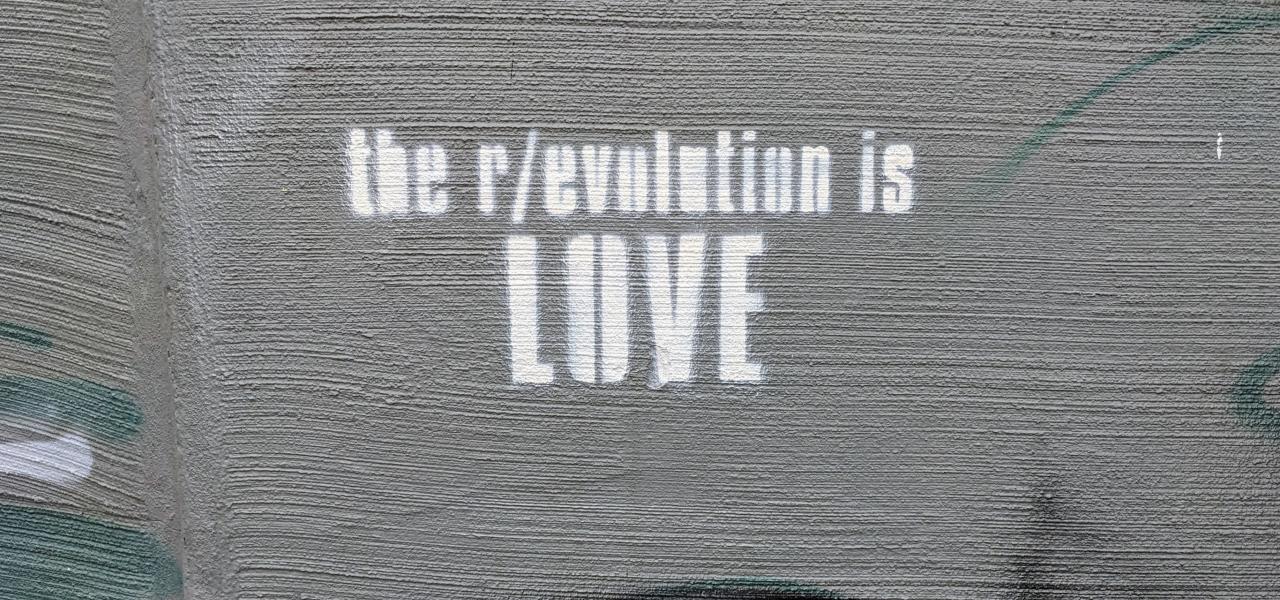

The revolution is already happening around us.

The arc of history over recent centuries has seen an unprecedented devolution of power from elites to the people. Tyrannies that once governed every corner of the world have in most countries been abolished. Democracy, until relatively recently considered a fanciful dream, has become commonplace. Within most democracies, oppression based on race, gender, sexual preference or religion is ever less socially or legally acceptable. We have witnessed the formation of the largest positive movements in history against racism, sexism, environmental destruction, cruelty to non-human animals, social injustice and war. We have come so far that Arundhati Roy’s statement seems tangible: “Another world is not only possible, she's on the way and, on a quiet day, if you listen very carefully you can hear her breathe”.

Progress is never inevitable, smooth or linear. Changes didn’t occur as inevitable forces of history. Society has moved forward only because individuals before us could conceive of a better world and took up the struggle to bring it into being. They often did so at great personal cost, generally opposed by the powerful and the majority of the society around them. If we can call our culture civilised it is partly the result of these free thinkers, rebels and outcasts who have dragged us to better versions of ourselves. We owe a debt to these often nameless people for much that is worthy in our society. The only repayment I can imagine worthy is for us to join our voice to their struggle for justice and fairness.

We need to continue the revolution. In discussing why I can only reflect properly on the society in which I live – a liberal democracy with high standards of living, an open press and the rule of law. I feel privileged to live in the place and time which I do. For all it's flaws, many people would look upon the freedoms and lifestyle within this society as impossibly utopian, and we should feel grateful for what has been achieved so far.

Scratching the surface of even our relative utopia, however, uncovers less ideal parts. The liberal democracy we cherish is manipulated by money and wealth. The high standards of living are unequally distributed and opportunity is still largely inherited. An open press exists but it is mostly run in the interests of the government and the corporations. Those with money also tend to find the rules of law often bend in their favour.

In a true utopia, we all could walk the streets at night unafraid; people who become sick could expect the best quality care regardless of income; homeless people would find shelter; children would receive a good education regardless of their parents’ status; people would not be incarcerated in brutalising institutions; billions of non-human animals wouldn’t be suffering and dying at human hands; the products and services we use would be made by people who have the advantages that we have; we would contribute more to the world beyond our borders; we would be living within sustainable ecological boundaries; indigenous people would feel respected and valued; we would be contributing to the vibrancy of the wild places and the wild creatures who share our world.

Whilst our greater potential selves are diminished living in a society with these problems, few injustices may directly affect well off individuals. Therefore whether the ones with the most economic power in society feel a need to act to stop these injustices can’t come from self-interest, but from their conscience and the limits they place on their morality. We have biases to favour members of our own groups, especially family as one would expect from evolutionary theory. In the modern world, however, we can see that the groups we consider ourselves a part of can be as arbitrary as sporting teams, companies, nations and religions. For good or ill our group bias can be manipulated quite easily. We must not only guard against others manipulating us by using this tendency but consciously foster within ourselves a positive and expansive group membership.

Einstein was clearly thinking about this when he wrote, “A human being is a part of the whole called by us universe, a part limited in time and space. He [sic] experiences himself, his thoughts and feeling as something separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty”.

Similar sentiments have a long heritage in our culture, though not always so beautifully and expansively put. Thinkers throughout the centuries have encouraged us to move beyond our self or family interest and foster a wider empathy within ourselves. This almost universally encouraged principle of consideration for others is replicated in our songs, stories, sayings, and fairytales, and encoded in customs and law. We like stories where good triumphs over evil because a social system of basic fairness helped us survive over the millennia. The universality of this theme is unsurprising given our evolution as a social being.

Selfishness may have been useful in some rare times of crisis, but in our everyday modern lives, it creates distrust, undermines social cohesion, and can create a more brittle social structure. Capitalism, a system that many of its adherents proudly declare to be based on selfishness, shows us how brittle selfishness is with its regular boom and bust cycles, and inability to fundamentally solve problems like poverty and inequality. The amoral mathematical logic of capitalism is just as happy to exploit people’s weaknesses for profit as it is to sell them goods which provide positive benefits.

The benefits there are of Capitalism stem from its basis as a natural system, but modern human society is anything but natural. No matter how destructively animals live in the wild, they simply don’t have the power to dramatically affect the global ecosystem. Human population and power makes living selfishly mathematically incompatible with the ongoing vibrancy of life on earth. Selfishness diminishes the beauty of the natural world, a beauty which provides such solace and joy in our lives. If we are serious about wanting to be a part of the resistance to the destruction of so much of life’s beauty, then we must take on a new self-identity and a new way of being. People talk about ideas like peace and love being important to them, but wanting them is not enough, we must act consistently and wisely to bring them into being in the world. We must be an activist, to think to ourselves as Fred Hampton so often said, “I am a revolutionary”.

Whilst taking on the role of an activist for positive change in the world is a necessary and fundamental first step, it is movements which make lasting change in the world. As Margaret Mead stated, it is always small groups of like-minded individuals that are the basis of movements for change. If we seek change then to have any realistic hope of achieving it we must join with others. This sounds simple enough, but it is not easy for many people. Schopenhauer's analogy of humans as hedgehogs, huddling together for warmth only to discover each other's spikiness, is an even better metaphor for groups of activists full of free thinkers and rebels, than it is for the general population. We should always be on guard against what Freud called the narcissism of small differences. In most groups disparate people are thrown together around a cause. We will find few exact ideological soulmates, but we will find many who share some or all of our core ethical principles. We need to support each other in overcoming our prickliness in order to maintain these groups for the long process of societal change. We may each have to give something of ourselves, without surrender, to enable us to work together. If we can create long term, positive groups, no matter how small, they will form the basis of a movement which will change the world.

We must know our history and remember that people who would change in society for the better rarely do so unopposed. Those who are benefitting from the status quo have obvious self-interested reasons to oppose meaningful reform. In a capitalist system where money translates so easily into power, change from below will not be easy; the powerful will discredit or co-opt our strategies with all the considerable resources available to them. The most effective way to start striking at the root of inequality is to remove the privileged access of the wealthy to influence. We must act to limit their donations to our political leaders, we must stop the revolving door of corporate appointments for obedient politicians once they have left office, and we must work to resist the corporate nature of our media.

We should not descend into the simplistic language of one class against another, for the world is not so simple as to correlate morality inversely with wealth. Superficial characteristics such as class are only peripherally useful. Many in the working classes would behave exactly as the elites in their position, because we all share a common humanity. It is that there are elites that we resist, it is the human desire to have status over others that is our enemy, not the few who happen to have that status. Instead of judging people by their economic class, we should judge people by their actions and to use Martin Luther King’s phrase, the content of their character.

Understanding people’s motivations is key to creating change. We cannot appeal to people to cast off the chains of their oppressors as Marx and Engels did in the Communist Manifesto, for it is not clear that they have any in modern liberal democracies. The successful resistance movements of the past relied on ranks mainly filled with those suffering direct, overt oppression. Our fellow citizens in privileged parts of the world have no pressing need to get involved in the struggle; indeed it may be against their own interests to do so, they would probably be better off conforming and enjoying historically unprecedented luxurious lifestyles. Thus our hope cannot be located in self-interest, which was always a simplistic view of human nature too often relied upon by progressive movements, especially unions.

Whilst we shouldn’t discard our in group identities, we should be ready to transcend them when needed. They will always be used by the powerful to divide and conquer.

Rather than appeals to self interest or group identity we must encourage people to care about greater themes, appeal to their empathy and their perception of themselves as fair-minded, decent people. We must tap into their higher selves, their sense of meaning and their place in the stories of life. Information is a powerful revolutionary tool, there are other tools often neglected when it comes to encouraging others to change. People learn most easily by example. As we model a revolutionary way of living in the world, both individually and in our communities, we can open up new possibilities for how to live. Our media informs but does not empower; this creates a feeling of hopelessness and without hope, people will not act. We must be a counter to this by giving people opportunities to make a tangible difference, partly to change the external world and partly to create a positive self-identity not related to consumption and competition. If we believe in our ability to create a better world, we need to prove it by example, building a model of it in our movement.

We must look to the long term health of our movement, and thus the people within it. The revolutionary life should not entail giving ourselves to a bleak view of the world. Emma Goldman was paraphrased “If I can’t dance, I don’t want your revolution”. She lived a life overflowing with beauty, love, lust and self-expression, and if anyone lived a revolutionary life it was her. Our lives and our movement should embody the world we wish to create. As the famous mantra of the Latin American struggle says, “we want bread and roses”. The struggle is more than the reduction of suffering, it is also about the proliferation of joy. It is imperative to find the right balance for our focus, to remember that our struggle is for the beauty of each individual life which together ultimately create the beauty of the world.

We will take the next evolutionary step together; whether it is forwards or backwards is down to the sum total of the actions of each individual. The only way I believe we can live meaningful lives is by joining in the healing of this world and all within it that can suffer. We have the knowledge to make a better world, we have the tools, we lack only the collective will to make it be. We are each faced with a choice: to play a part in the revolution towards equality amongst people and empathy for all that can suffer, or support selfishness and thus the status quo or even regression. Amidst the march of history there is no neutral place to stand; for good or ill our actions ripple out into the world. With our labour, with our time, with our consumption, we are supporting some vision of the world, consciously or otherwise.

If one seeks a meaningful life, to contribute to a better world for all living things, one must define oneself, one must draw a line, one must face the mirror and ask “Who am I in these revolutionary times?”.